Ivan T. Sanderson — Chapter 12 — "And now young man, you are going to be on my radio show."

After our talk, Ivan Sanderson escorted me out to the kitchen where he opened the refrigerator and brought out a pitcher of something dark. He poured this substance into a large square glass until it was full, then handed it to me and said: “This will give you something to suck on for a while.”

I cautiously tasted the fluid. Fortunately, it was ordinary cider.

“Now young man,” he said, “you are going to be on my radio show. I like your style of interviewing and your knowledge of forteana.”

Still in a daze from the information overload of the proceeding four hours, I wan't quite prepared for this news, and thus, I took Ivan's announcement with the proverbial grain of salt. I just said (rather suspiciously, I’m afraid), “Really. That’s all I need, a radio show.”

Alma, who had just entered the room, approached me and said, “But he really means it!”

“He does?”

“Of course.”

“Just a second folks,” I replied, “let this sink in first... Give me a chance to recover!” I neglected to mention to them that, prior to this elated moment, I had always thought of radio as being a “worthless” entertainment medium!

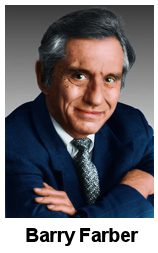

The radio show Ivan was referring to actually belonged to the well-known conservative talk show host (and friend of Ivan), Barry Farber, himself a fascinating fellow who is a student of about 25 languages. As it happens, in 1970 Farber was running for Congress in New York City's 19th district on the Republican ticket, but was defeated by Bella Abzug. During the campaign, Farber was absent from his show much of the time and employed guest hosts to fill in for him. Ivan Sanderson hosted the show every Thursday night for 20 weeks, from 11:30 p.m. to 2:00 a.m. The show originated from WOR-Radio in New York, but was broadcast to stations in 38 U.S. states.

The radio show Ivan was referring to actually belonged to the well-known conservative talk show host (and friend of Ivan), Barry Farber, himself a fascinating fellow who is a student of about 25 languages. As it happens, in 1970 Farber was running for Congress in New York City's 19th district on the Republican ticket, but was defeated by Bella Abzug. During the campaign, Farber was absent from his show much of the time and employed guest hosts to fill in for him. Ivan Sanderson hosted the show every Thursday night for 20 weeks, from 11:30 p.m. to 2:00 a.m. The show originated from WOR-Radio in New York, but was broadcast to stations in 38 U.S. states.

I was then shown into a room which was partly an office for his then-assistant, Marion Fawcett (she was no relation to the Colonel Fawcett mentioned previously—she eventually became Ivan's second wife following the death of Alma) and partly a storage area for what was SITU's collection of thousands of reports on UFOs, sea monsters, yeti, and all sorts of as-yet unofficially recognized creatures, all neatly catalogued on shelves that took up an entire wall, and more. I just stood there, flabbergasted at all of this unexplained material, while Marion sat on a pillowed old chair, faced an older desk, and typed on a still older typewriter. After a few moments of coaxing the machine into doing her bidding, she handed me a little yellow card which read:

Card No. 497H

Expires —

THIS CERTIFIES THAT THE BEARER, Richard Grigonis, IS A MEMBER OF THE SOCIETY FOR THE INVESTIGATION OF THE UNEXPLAINED, COLUMBIA, NEW JERSEY 07832

Beneath this was Ivan’s personal signature. I now found myself a member of Ivan's motley group devoted to exploring the unknown; and I was an Honorary member at that, which relieved my wallet considerably.

My father and I shook hands with the staff, thanking them for all they had done. With cheerful good-byes we once again drove off, back to civilization.

The next week found me preparing feverishly for my debut on WOR-Radio. In my haste and excitement, I had neglected to find out what the program’s topic of conversation was going to be! Ivan rang up to inform me that I would be appearing on his next show, which was on Thursday night. We were going to talk about sea monsters, he said.

“But Ivan,” I said, “I’m not exactly what you would call the world’s greatest living authority on sea monsters. The least I could do would be to brush up on some of the more recent reports.”

“Don’t worry Richard, I’ll send you Bernard Heuvelman’s book, In the Wake of the Sea-Serpents and an article of mine on a recent sighting on sonar off the coast of Alaska. You’ll be fine,” he assured me. “And why don’t you bring your father along for the ride? See you.” Since I was too young to drive, that was a sensible suggestion.

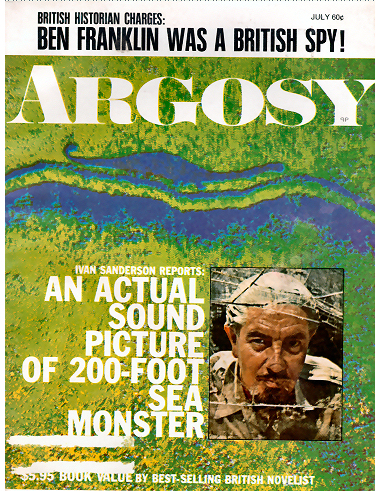

Sure enough, a few days later a cardboard box came in the mail containing Heuvelman’s book, plus the tearsheet of an article that Ivan had done for Argosy Magazine. On the magazine’s cover there was a greenish-blue “echogram” of something that had the classic outline of every old sailor's vision of a sea monster, complete with flippers, tail, and a brontosaurian neck. There was also a photo of Ivan on the cover, appearing as if it had been taken through a broken glass window (no doubt to add a bit of melodrama or at least accentuate the seriousness of the subject to those readers who might think the whole thing to be a lot of tosh).

Sure enough, a few days later a cardboard box came in the mail containing Heuvelman’s book, plus the tearsheet of an article that Ivan had done for Argosy Magazine. On the magazine’s cover there was a greenish-blue “echogram” of something that had the classic outline of every old sailor's vision of a sea monster, complete with flippers, tail, and a brontosaurian neck. There was also a photo of Ivan on the cover, appearing as if it had been taken through a broken glass window (no doubt to add a bit of melodrama or at least accentuate the seriousness of the subject to those readers who might think the whole thing to be a lot of tosh).

The article told of how a fishing trawler cruising off the coast of Alaska had been using a sonar device (called Simrad) to locate fish. This remarkable little machine can scan a cross-section of the ocean right down to the rocky bottom beneath the sediment, recording what it “sees” on a strip of paper, all while the ship sails along on the surface.

Schools of fish show up as a sort of granular cloud on the paper, and anything larger that is solid shows up in outline. On this occasion the machine scanned, in addition to the ocean bottom and some fish, an outline of what appears to be a giant plesiosaur or perhaps a giant sea-lion (pinniped) that by calculation assumes a length of over 200 feet! Ivan was rather proud of this little sheet of paper, since he thought it constituted concrete evidence of the existence of sea monsters. The image on the paper had begun to fade away, but Ivan had photographed it many times, even making large prints of it for a more detailed examination. This echogram and other sightings of strange sea creatures would be discussed and debated on the show.

The plan was to first rendevous with Ivan and Alma in their New York apartment, where I would be introduced to the other guests who were to appear on the show. We would then have dinner at a restaurant, afterwards proceeding to the WOR Building.

Ivan Sanderson's New York Apartment

Aside from some amusing stories about escaped skunks and keeping a hippo in the basement for a week prior to its appearance on a TV show, Ivan's New York apartment is probably an enigma to this fans. Just about everybody knew he had it, and many famous friends of his visited it (e.g. Sir Edmund Hillary, conqueror of Mr. Everest), but few people today know what it looked like. That's why I'm now going to present what some readers may consider an unusually detailed account, based on my notes of the time and best recollections, of a visit to Ivan Sanderson's New York City apartment, in August of 1970.

It was now a hot Thursday in August, the day of the radio program. My father and I left home after lunch and traveled down the 60-mile ribbon of highway to New York City with little trouble and/or traffic. We drove our car onto one of the parking lots that existed in those days atop New York's Port Authority Bus Terminal, got out (carefully taking note of our car’s position so as not to lose it later) and walked toward the elevators. Everything was going along smoothly, and I felt confident that going to see Ivan in "The City” would be easier than the pilgrimage necessary to meet him near the Delaware Water Gap.

Well, not quite.

First, the elevator refused to come up to the Port Authority’s upper parking lot. When it did, the door opened and out fell a thoroughly intoxicated fellow who smelled like a gas station. My father and I stepped into the elevator, a shiny white cubicle devoid of any decoration. There were six little black buttons, though, and I pushed the bottom one. The machinery whirred, the lights flickered, and the elevator car whisked us to the ground floor.

For those who are either too young or too old to remember the grimy, decaying, art deco interior of the New York Port Authority Bus Terminal prior to its pre-1979 expansion and revitalization, it was an experience, let me tell you. When an elevator door opened on the ground floor, a person unfamiliar with the building got the impression of standing at the back of a narrow, squared-off version of the Big Room at the Carlsbad Caverns, tiled over to resemble some vast public toilet facility. Today we would compare it to a dank shopping mall.

Impressed by the bus terminal's block-long immensity, we began to head for the front door, which, from where we were standing (near the Ninth Avenue entrance) seemed to be only a mile or so away. We had to work our way through myriad little crowds of people clustered around the buying and selling areas, soda machines, and the mens’ and ladies’ rooms. After a hectic five-minute walk we finally made it to the expanse of glass doors that opened onto Eighth Avenue.

Now, as much as I adore New York after having worked there from 1979 to 2003, New York in 1970 was a different matter. It was a mess. At that time, long before the great renaissance that transformed the Port Authority area, Times Square, the theatre district, and Hell's Kitchen in general, nearby pornographic video stores and peep shows made that area Manhattan’s answer to the Tenderloin district of San Francisco. I ventured into it only when I had to to see museums, orchestras, operas, zoos, Broadway shows (e.g., Ethel Merman's final role on Broadway in "Hello, Dolly!") and Ivan’s irresistible radio offer. You passed by all sorts of bizarre characters walking on the streets, and the air seemed dirtier than it is today. Carbon and sulfur dioxides have never bothered me at all, but the particulate matter—the dirt—floating around over the sidewalks always got in my eyes. This particular trip to “Fun City” was no exception. (I love that preposterous name, coined by Mayor John Lindsay in 1966, and used derisively until it was dethroned by “the Big Apple” in the 1970s.) Hence, there I was, wiping my eyes every half block or so. Why didn’t I bring sunglasses? It was about 4:00 p.m. and the commuter traffic was starting to thicken the streets, impeding our progress.

Ivan’s apartment was in the Whitby Buiding at 325 West 45th Street, between Eighth and Ninth Avenues. Architect Emory Roth, allegedly inspired by the Athenian Choragic Monument of Lysicrates, had designed this 11-story brick structure, constructed in 1923 by Bing and Bing. Situated in the very center of New York's theatre district, the building was favored by theatre professionals. Its former residents include Doris Day and Betty Grable. Still living at the Whitby in 1970 was Benny Goodman's saxophonist, Nuncio ("Toots") Mondello, who had moved there in 1934.

Although Ivan was never interested in investigating the "intangible" unexplained phenomenon of apparitions, Whitby residents claimed that ghosts of actresses who had died there would regularly summon an elevator to the building's sixth floor.

Our visit to the Whitby occurred 15 years after it had ceased to be a fashionable New York address, and 15 years before it again became fashionable as a revitalized cooperative in a regentrified neighborhood. Given the amazingly bad publicity New York was getting at the time, out-of-towners could easily be terrified. Summoning all of our courage, we strode into its front door, our nerves and muscles tensed, waiting for some imagined menace to leap at us from the shadows. We entered into a small dark room, a desk occupying the entire right wall. On the desk was a dialless black phone. Today I would recognize it as a Western Electric 300 desk phone of 1940s or 50s vintage. No one was around.

The lobby in which we were standing had certainly seen better times in some bygone era of New York. It had been painted a pale beige too many times over the years, from its ceiling to the rutted floor beneath us—including windows, doors, et al.

I did not know Ivan’ s apartment number—he had not given it to me. I simply picked up the phone and said the name "Sanderson." Without comment of any sort from an operator, a few moments of waiting and silence yielded the ringing of a phone at the other end of the line.

Alma answered: “Come up to the fifth floor, apartment number 516.”

I thanked her, hung up the phone, and we walked over to a door in the wall. This door wasn’t like any of the others in that room, for it had a circular porthole-type window. I pulled on a handle and the door swung open. This was the elevator. We got in that ramshackle little thing, which was slightly more spacious than a phone booth, and I pushed a large black button with what must have once been the numeral five gold-leafed on its surface. The well-worn machine then shook, lurched into the air a few inches, stopped, and the lights went out. I frantically reached for where I had pushed the button and slapped the wall. The contrivance came back to life, chugging, squeaking and rattling as it lifted us to the fifth floor. We made our way down a hot, narrow corridor to Ivan’s apartment.

The apartment had originally belonged to a gangster back in Prohibition days, which explained the presence of the massive steel door before us.

I rang the bell. The noise of locks opening could be heard on the other side. The door then creaked open, and there stood Alma.

“Hello there! Come in and meet everybody,” she said, gleefully.

We left the sauna-like hallway and entered an apartment that could have passed for a blast furnace. The living room was small, but it had the same “museum” atmosphere as its counterpart back in the wilds of New Jersey. Vaguely resembling an old, ornamented vestibule to the Smithsonian Institution, it was finished in a plaster motif, with long sepia drapes ornately concealing the small, ripple-glass windows. There was some worn carpeting that still gave hint to the fine, exotic materials that had once glittered up at visitors, and every stick of furniture in sight was enveloped in faded slipcovers.

To my left was a piece of wood that was shaped like a camel.

“That piece over there was not carved,” said Alma, resuming her role as tour guide. “Oh no, that is a root of a tree that has grown into that shape…Looks just like a camel. We found it on one of our expeditions.”

I was amazed—I was also hot. I looked over to an ancient fan on top of a small bookcase. It was doing its level best to pump the sweltering air around the room, worsening the situation.

“Tell me, Alma, this entire apartment wouldn’t happen to be a giant Japanese sweat box that Ivan picked up during the war, would it?”

“Oh no Richard, ha ha. Why don’t you go in and meet the guests for the radio show. They’re all in the bedroom.”

“In the bedroom? Why is everyone in the bedroom?”

“Because that’s where the air conditioner is, Richard,” she said. Before Alma had finished her sentence, both my father and I dashed into an alcove-kitchen. I darted to the left—and ended up in the bathroom. My father on the other hand, went to the right and disappeared through a doorway. I passed back through the kitchen and did the same, running smack into air far colder than what a window air conditioner should be able to produce. If the living room was a furnace, this bedroom was a freezer. Four men were sitting on the bed, shivering. Alma came into the room and introduced them to us.

A man named Carlsen representing the company that imports Simrad was there, and so was a cheerful short fellow from the Bureau of Commercial Fisheries of the Department of the Interior. Dan Manning the photographer/newsman was there, and so was Michael R. Freedman, a member of the SITU Resident Staff and Governing Board who had finished up a four-year stint in the U.S. Naval Reserve as an electronics technician. Missing were Ivan and the former editor of Science Digest, Daniel Cohen.

After spending a few chilling minutes in the bedroom, it was suggested that we brave the fiery heat in the living room for a while, since Ivan would obviously be coming back shortly and we would be moving on to the restaurant. To this everyone complied, and I greedily made sure that I got a seat as close as possible to the fan. We all began to talk.

A short time later the front door burst open and in came Ivan, beaming and transfusing some life into whatever the topic of conversation was. I suppose you could have likened it to a subtle “grand entrance.”

He was pleased to see that all of us had made it in time, mentioning in the same breath that Daniel Cohen would join us later at the studio.

“Have you brought me back the Heuvelmans book?” he asked.

“Right here Ivan,” I replied, as I quickly thumbed through the few notes and other belongings that I had toted along with me on this venture. I found the book and handed it to him. “Thanks for letting me study the book. I could never even have thought about doing a talk show on sea monsters without ‘brushing up.’”

“Anytime, Richard,” said Ivan, in his best British accent.

Obviously, Ivan was doing some “brushing up” of his own, polishing his elocution in preparation for the long grind of having to maintain nearly two and a half hours of conversation with his guests on the air.

Have Indigestion, Will Travel

Looking at his watch, Ivan then advised that we should start down to the restaurant. With growing appetites, we all got up and began to evacuate the premises, spurred on by the promise of a free dinner, courtesy of Ivan.

“We’re going to a Greek restaurant tonight!” bubbled Alma.

Famous last words, I thought. I normally like Greek cuisine, but I was having a premonition that this evening would be different. Indigestion lay ahead.

“I guess I should have brought along my alka-seltzer,” I remarked, somewhat jokingly so as not to upset anyone’s feelings. For some reason I expected the worst in the way of epicurean delights now, and I sure got them.

We all piled into the elevator. I am not at all certain whether anyone pushed a button or not, but the elevator car immediately began to fall back down to the ground floor. Once there, we passed through the still vacant lobby and strolled out into the street. It was night now, and this particular side-street to Hell’s Kitchen was devoid of traffic. There were, however, two street gangs— each gang comprised of from ten to fifteen boys—on the street in back of us.

We did not linger to find out what was going to happen. Instead, we had a leisurely walk into the theatre district. I saw Sardi’s in front of us, and I jumped to the conclusion that Ivan had changed his mind about his choice of dining establishments for the evening, which was a relief. He hadn’t. We walked right past Sardi’s and continued down a darkening street. Soon we came upon and entered a Greek restaurant that shall remain nameless. It was about as wide as a bus and twice as long, darkly lit—and full of people, smoke, and noise. On the far two walls were murals of supposedly impressionistic scenes depicting the buildings and people of ancient Greece. There were dark wooden tables covered with coarse white tablecloths and napkins, and walnut dividers could be seen randomly distributed throughout the single tunnel-like room that did not quite contain the cloudy mass of suppressed pandemonium within its four walls.

A waitress escorted our party to a long table at the rear of the restaurant. We all sat down and were given menus. No one could read them however, because the minute lights above us were pointed at the walls. Besides, the names of the foods were in Greek. Ivan, seated at one end of the table next to me, said, “Order this, it's delicious.” He pointed to some name on the back of the menu.

“I guess I’ll have the same,” said my father.

“If they’ve got any steak in this place, I’ll have some,” said Mr. Rossoli, the man from the U.S. Government. My father and I, following Ivan’s gourmet advice, allowed him to order for us the “delicious” dish.

I could hear music—Mikis Theodorakis' theme from Zorba the Greek. The tempo was beginning to build and I could see feet at neighboring tables start to hop. I gazed across the room to see a reel-to-reel tape recorder operating behind a large plastic bush. By the look of its large reels and slow tape speed, that machine could have played all day, non-stop, and probably did. In the meantime, Ivan was complaining that the first edition to his latest book would consist of a printing of only 50,000 copies! This was turning out to be quite an evening.

My merriment ended when the food was brought out. Mr. Rossoli dug right into his order, which was something that resembled a whole side of juicy beef. My father and I, on the other hand, each received a bowl of rice from our waitress. On top of this rice lay chicken livers. Covering that was some black gravy. That was it.

I could hear Rossoli praising the tenderness and flavor of his dinner, despite the fact that he was at the other end of the table. My father and I began to devour the allegedly delicious dish. Unspectacular flavor, but quite edible.

Ivan then began to order the drinks. He asked me what I wanted.

“But Ivan, you know I'm too young to drink.”

“Oh, I see. When I was a boy in Scotland, everybody your age was drinking. Why, they were all practically alcoholics. How about a cigarette?”

“I don’t smoke either.”

“Oh?”

Just then my father jumped in with: “As a matter of fact, Mr. Sanderson, Richard has been trying to get me to quit smoking for some time now.” Being a bit hard of hearing, he tended to speak loudly.

Ivan retreated at this remark: “All right, Mr. Grigonis, I believe you, you don’t have to bark.” Perhaps he was also overly sensitive on account of the upcoming show. After all, it was his third program of this new series. Perhaps in an effort to calm himself, the veteran of hundreds of past TV and radio broadcasts then proceeded to down seven glasses of seven different types of alcoholic beverages. (Actually, Ivan had eight drinks. As I learned later from one of his close associates, each member of the radio program who was having dinner with him every week found a glass of water set before him. Prior arrangements with the waiters ensured that Ivan’s glass was continually filled with straight gin).

His fourth drink, Drambuie, was a little darker than the others, and so he began explaining to us its historical origins: “You see, back in the days of yore, somebody killed a goat that had eaten nothing but a certain kind of grass and took out its third stomach and put it in a log to ferment for six months and this was all done without sugar and...”

While Ivan rambled on with this rather lengthy history, I turned to Mike Freedman and Dan Manning, who were talking about a girl who could “feel” colors with her hands. I entered the conversation with: “I’ve heard that the girl you are talking about could perform the color tests with a blindfold, but not with an aluminum box over her head that made the test completely foolproof.”

Freedman turned to me and said, “Perhaps the aluminum disrupted an electromagnetic influence that might have something to do with her power.”

“Or,” I quipped, “perhaps somebody’s been peeking under the blindfold.”

Ivan, finished with his near-Homeric story about the origins of his drink, now began to tell some stories about Greeks.

“Once Mike Freedman and I stayed at this hotel,” began Ivan. “The place was full of these gentlemen who were in town for a convention of some sort. The whole building was full of tobacco smoke, and we couldn’t get any of the windows to open. We finally got hold of the janator—a Greek—and he opened two of those damned things for us. A little later, the window in our room slid down and shut. We got it open again, and this time we propped it open with a Gideon Bible—there’s one in every hotel room, you know. A few minutes passed, it now appearing that we had cleared all of the smoke from our room. Just then we heard the window slide shut. We ran over to it and looked out, seeing a very disgruntled policeman on the sidewalk below, along with his smashed officers’ hat and the Bible, which was sitting there opened up to Isaiah or something. The policeman bent over the Bible and examined it carefully—I guess he thought that he was receiving a warning from Providence!”

It was now dessert time. “Order this, it’s delicious,” said Ivan, in a repeat performance of his now infamous line. I did—with similar consequences as before. My father wrangled out of ordering it by suddenly disappearing into the men’s room.

I was soon brought a small plate on which lay a pile of old, soft graham crackers covered with some antediluvian honey. I took one bite and nearly spat it out—it tasted like moldy cardboard. I ordered a Coke. With it, I somehow managed to wash down a third of the stuff. I ordered another Coke—a large one. Another third of the dessert disappeared. I then prepared to order yet another Coke.

Alma, who had been eyeing me suspiciously during my torture session, said, “I wouldn’t order another Coke if I were you, Richard. You can’t fight sweetness with sweetness—it will make you sick.”

I felt like telling her that if I didn’t order another Coke, this cardboard-and-honey concoction would make me sick anyway. Still, not wanting to hurt anyone’s feelings, I abstained from requesting the soft drink and instead drank an entire pitcher of icewater. Through the corner of my eye I could see Freedman staring incredulously at me. I put my glass down and said, “That certainly was the most delicious pitcher of water that I have ever tasted in my life. It's true what they say about New York tap water.”

Freedman, sensing my distress, chuckled.

I looked at the remaining third of my dessert. I simply could not finish it. The waitress then came, gave Ivan the check, and started picking up the dishes. She spotted my dessert.

“You no like?” she asked.

“Me no like,” I joked. My father had just reappeared.

It was 10:00 p.m. now, and Ivan wanted all of us to go back to the apartment for a while so that we could prepare for the show. We agreed, and our little party of seven once again ambled off into the darkness. Bounding the corner at Eighth Avenue, we saw the apartment building—and now three gangs of kids where there had been but two an hour before. Sensing danger, I wanted to get into Ivan’s firetrap as soon as possible. When I neared the door, however, fate struck again.

“Just a second Rich,” said Dan Manning. “I want to show you the bookstore across the street. They’ve got a lot of books on unexplained phenomena—there are even some of Ivan’s books there.”

“I don’t think so,” I said, keeping an eye on the gangs.

“Come on, it’s just across the street over there,” he urged, pointing to a building just in back off all three assemblages. Our party had just gone into the apartment and was waiting for the elevator.

Reluctantly, I agreed. We passed by one gang. Nothing happened. We passed by another gang. Still nothing happened. We approached the third gang. My knees were beginning to shake. Don’t collapse now Richard, I thought, or they’ll tear you to pieces and steal your dime. We passed the third gang. Nothing happened. I kept looking back, making sure that some enterprising individual was not attempting to sneak up on us from behind. They all just seemed to be ignoring us.

We finally crossed the street to the bookstore—“The Flying Saucer Bookstore.” It was closed. Before turning around I heard Dan exclaim that Ivan’s book, More Things, was displayed in the window, and quite prominently at that. Wonderful. I already had a copy of it, given to me personally by Ivan.

Now all we had to do was to squeeze by the same three parties, who were still kicking around in the middle of the street. I swept past them in a flash, leaving Dan to defend himself alone should trouble arise. I got to the front door of the apartment building in no time at all, but I waited at the threshold for Dan, since I was not sure what might be lurking inside.

We entered, all being quiet in the lobby as usual. Following another death-defying elevator ride to the fifth floor, we rejoined the rest of our group back at the apartment. Everyone was sitting around, chatting. I got talking to Ivan about a Lithic stone implement field in British Honduras (now called Belize) he had written about. He went into the bathroom for a moment and returned with one of the stone spearheads from that field. We then discussed such things as Thor Heyerdahl’s sighting of a UFO near the Azores (Heyerdahl had launched his ship, Ra II and was sailing across the Atlantic from Morocco at the time, attempting to prove that prehistoric Egyptians could have sailed to the New World).

“You know,” Ivan said, “Heyerdahl is a funny sort of fellow. He wrote of floating over this ‘mass’ of something in his book, Kon-Tiki. He said it probably was the ‘ray of evil repute’—whatever that is— but then he contradicted himself by saying that it split into two parts which then swam around his raft. Well, after SITU pounced on this, he didn’t talk about it much anymore. Now you tell me he’s seen this flying saucer thing.”

It had never occurred to me to observe Ivan’s apparel for the evening. I had noticed earlier that his clothes were a little old yes; but now that I was closer to him I could see that he was barefooted besides, and he was wearing a peace medallion on a chain around his neck!

“Darling, why don’t you change your shirt or something,” said Alma.

Ivan answered definitively: “No.”

Nonplussed, Alma did not press the matter further. Here was one of the small gestures of tolerance that had kept the couple in marital bliss for the past 36 years.

10:45 p.m. came and went. Show time was 11:30.

Into the Ether

The decision was made to head for the studio. Alma told us she would stay here at the apartment and listen to the show on the radio. The six of us then had another adventurous elevator ride to the ground floor, after which we again stepped out into the warm, noisy, New York night. Following a few minutes of walking, we cut across 42nd Street near the Allied Chemical Building (now called One Times Square), soon ending up in the lobby of the WOR Building. We all signed in, stepped into a sleek, brightly lit elevator, and a moment later we were on the seventh floor. The corridors, many of which were covered with sound-absorbing ceiling tiles, were so narrow that a man of large stature would have to pass through them turned sideways. After a few left and right turns, we found ourselves in a sound room where two men were twiddling dials and flicking switches. There was a large window where the actual studio itself could be seen, the one that normally occupied Barry Farber and his guests. As I mentioned previously, Farber was running for Congress against Bella Abzug at the time, so selected guests were hosting the show in his absence. Ivan was on every Thursday night for a scheduled 20 weeks.

Ivan swung a door open and we entered the studio down a carpeted ramp. The room was covered with acoustic panels (the kind with holes that you see on some old ceilings) and, consequently, there was not a window in the place, except for the one through which the two soundmen could send you messages in their own language of hand signs. There was a large clock ticking away beneath this window that read 11:15 p.m., and in front of me there stretched a long curved table with about seven chairs on the convex part for the guests, each facing the one chair on the other side (the concave part) that normally seated Barry. To the left of this lone chair was a panel on which there were about ten small dials. A chair had been conveniently provided in a corner for my father.

Sitting on a far chair at the table was a man in his late 20s or early 30s, in casual attire. I nudged Ivan and asked, “Who is that? Cohen?”

“Yes. That’s Daniel Cohen. He used to bully me when I tried to write fortean articles for his magazine, and now that he’s written a book on sea monsters—well, let’s just say that I’ve got him right where I want him!”

“Oh.”

“By the way, Richard,” he went on, “the producer of this show is positively tickled pink to have you on—especially after what I told him about you.”

“What are you talking about?”

“Well, let’s just say that we’re going to put one over on him. That’s how I got you in here. Just wait until I introduce you, you’ll see.”

I was not sure what he had meant by that, but I would find out soon enough—it was air time. Meanwhile, 60 miles away, my poor English teacher friend, Mildred Hughes, was trying to gather some of WOR’s 50,000 watts of power on her car radio. There she was out in the darkness, the time now 11:30 p.m., running the motor and radio just so she could record my voice on a cassette tape recorder, and probably having second thoughts about ever introducing me to that “eccentric guy past Blairstown.” Seated next to her was her daughter and the family's pet racoon. Lightning storms in the distance were generating static in WOR-Radio's AM band, disrupting the quality of the recording.

Back in Farberland, we were all now seated, patiently waiting for the show to begin. One of the men behind the window made a gesture. Ivan made one back. Nothing was happening. A few tense, silent moments passed, then Ivan leaned over to his microphone and proceeded to launch the show. After introducing a number of guests, he came to me. All eyes in the room were now on me. They were finally going to discover why a 12-year old kid was appearing with them on national radio. The following then echoed throughout the ether:

“Then I have with me Mr. Richard Grigonis: G-r-i-g-o-n-i-s, who is a universalist. He also has his own radio show using tape like Walter McGraw does, for interviews. Mr. Grigonis is doing some extraordinary work in the educational field. He’s a sort of neighbor of mine in Newton, New Jersey, with the schools around there. Richard Grigonis. I believe I’m right in saying that this next fall you’re starting in the ninth grade?”

“Yes, the ninth grade,” I replied

“The ninth grade,” Ivan echoed with proper definitiveness, delivered with a straight face.

Ivan went on with the other introductions, none of which being as unusual as the one he had inflicted on me.

Though my credentials had been expanded considerably, I did not bring up the subject, preferring instead to savor the amazed look on everyone’s faces. It has been so many years since the show that I do not remember the exact sequence of events that immediately followed, but I do remember that a soundman behind the window looked bemused for some reason when he heard my intro, and everyone on the panel (except for Ivan, who kept a straight face throughout) clandestinely stretched across the table to get a good look at me. No wonder the producer of the show was “tickled pink” to have me on this program!

What followed the introductions was one of the more exhausting shows in the history of radio broadcasting—well, it seemed that way. During a radio show one's attention is intensely focused on the subject at hand as you try to formulate a quick-witted remark or two in case the show's host suddenly decides to call upon you for a response.

But, this was a civilized show, unlike some of the firebrand broadcasts of today. No flaming comments here; aside from some amusing commentary, it was basically a long, drawn-out, erudite radio panel discussion on every reported aspect of these creatures that are said to lurk in the briny deep. Of course, no discussion on this subject would be complete without a short dissertation on that perennial favorite of freshwater monster enthusiasts, “Nessie” of Loch Ness. Ivan and Dan Cohen took care of that by dragging out all of the “classic” sightings of this lovable tourist attraction which usually confines its peregrinations to a 400-foot-thick layer of algae at the bottom of the loch, at least according to a number of sonar surveys and an RAF report.

At 1:00 a.m. I looked around the room to see my father sleeping on the chair in the corner. I hope he wasn't going to start snoring. Turning to my left, I could see Mike Freedman snoozing away at my end of the table. I myself had become tired, but I dare not drop off into slumberland right now, for this show was all live, except for some commercials that were taped and narrated by Barry Farber. Besides, I was about to deliver my own little proclamation on the subject:

“Up until now you’ve presented us with a pretty convincing argument for sea monsters being pinnipeds,” I began. “However, there are a good many incidents which have taken place involving humps or a set of loops sticking out of the water and moving at great speed. This can only be attributed to the existence of some species of giant eel. Now, a ship called the Dana once caught an eel larva over five feet long. If this had been allowed to grow, the adult would have reached 150 feet in length, and you would have had yourself a ‘sea monster'.”

“Yes of course, Richard,” Ivan replied. “But you must remember that the vertebrate of eels are such that they cannot undulate their bodies up-and-down as would be required for those reports. They can only undulate sideways.”

“Well Ivan, perhaps they swim on their side,” I said, rather foolhardily.

“Or perhaps the vertebrate of these big boys are different than common eels,” said Ivan, accompanied with a faint smile, for that line had saved my whole argument. He then returned to his talk with John Carlsen, representing the company that imported the sonar device Simrad.

At first I expected a wild argument over whether the machine that had seen the monster off the coast of Alaska had been faulty, and if it had not been faulty then the monster must be real—a line of reasoning that any Fortean would use against a skeptic. What we got instead was a pleasant soliloquy from Mr. Carlsen admitting the possible, perhaps probable existence of sea monsters. Why? Well, he explained to us that shortly after Ivan’s article on the Alaskan monster and its illustration of the echogram appeared in Argosy, scores of private individuals, companies, universities, etc., had all put in orders for Simrad equipment, each wanting to be the first on their block to have sighted a sea monster. The general upswing in business was amazing, said Mr. Carlsen. The formerly substantial cry of: “There ain’t no such animal,” had been instantaneously transformed into: “Sure there is, so why don’t you buy one of our machines and find a monster of your very own!”

Shortly after 1:15 a.m. we again paused for a commercial. Someone came into the studio with a tray of pastries as a sort of early-early-morning snack. I tasted some of the tidbits.

“God is this stuff stale,” I remarked. Everyone was chattering away like mad. Not a steady hum of dialogue but bits of spontaneous talk that crackled like popcorn in the making.

Suddenly a man behind the window made frenzied gestures. Ivan put his hands up to his head in astonishment and told us all to keep quiet for a second. Our mikes might have been inadvertently “left open,” and our conversations could be intermingling with Barry Farber’s commercial. If that were so, it would be the only high point of the evening. Sitting there, I visualized a great radio blooper: You hear Barry Farber’s voice begging you to run right down to such and such a restaurant, and then you hear the voices of the supposedly satisfied customers, including my: “God is this stuff stale!”

A few more gestures came from the control room, and Ivan reassured us that everything was all right after all, and we would be continuing with the show in a moment. So much for the evening’s excitement.

A few more gestures came from the control room, and Ivan reassured us that everything was all right after all, and we would be continuing with the show in a moment. So much for the evening’s excitement.

Finally, at 2:00 a.m., the show came to an end. Even after all of this profound discussion, sea monsters remained an enigma. I walked over to Ivan to say so long.

“I’ll be seeing you Ivan—and thanks for everything.”

“Good-by, Richard, and good luck.” His tired, limpid eyes were staring through me and he was forcing a big smile. As I turned away from this weary soul, I suddenly realized that Ivan had put on a remarkable performance. He had talked for hours using no notes whatsoever, and with a considerable amount of alcohol in him besides. How could he have kept up this pace for his entire life?

My father and I then departed the studio, took the elevator down to the ground floor, signed out of the building, and walked down 42nd Street back to the Port Authority Building, which was an experience itself in those days, especially at that hour of the morning. At the back of the terminal we found our now-familiar aquaintance, the drunk, who was blocking the elevator entrances on the ground floor. We had to nudge him out of the way to gain access to the elevator, which soon took us up to our car on the roof. We then drove out of New York, and somehow made a wrong turn, and were lost for three hours. After a series of misadventures on New Jersey’s overly complicated highway system, we made it back home. It was 6:00 a.m. now, and dawn was filtering through the trees. I collapsed onto my bed.

Ivan continued hosting the Barry Farber show for the scheduled 20 weeks. Farber lost the election, tried running for office of Mayor of New York in 1977 but was again defeated.

At the end of the show’s run, Ivan's apartment was stripped of its office equipment, books, and furnishings of great intrinsic value, which were then transferred to the Annex Building at SITU Headquarters. After Ivan's death in 1973, Ivan's friend Roy Pinney, the photographer and "father of herpetology," moved into the apartment at the Whitby with his own collection of lizards and strange creatures. A few years ago, Pinney, now in his 90s, turned the apartment over to his nephew, and moved into a Park Avenue pad with his wife.

In 1996 Yours Truly finally had occasion to meet Barry Farber. I had lunch with him at a restaurant on 21st street near the Flatiron Building in Manhattan and we traded stories about Ivan Sanderson.

"I started my radio broadcasting career in 1960," he began, "Just before that, I read an autobiography of radio commentator and journalist Mary Margaret McBride. In it she wrote that Ivan Sanderson 'was the most fascinating guest she had had on her show in 20 years.' Naturally, I was determined that one of my first guests as a radio host was going to be Ivan Sanderson."

"Did you ever visit him?" I asked.

"Yes, I made the trek to New Jersey," replied Farber. "When you walked into his home, there was a line of people sitting outside a room, waiting to see him. It was like in the days of ancient Rome, when a long line of people would wait in the foyer of a great man's home, seeking an audience. They all had strange objects or animals or ideas to discuss with Ivan, all of them seeking notoriety, money for research, or just some kind of recognition. One fellow did nothing but collect reports of strange coincidences. He said he had invented a sort of Richter scale of coincidence, called the K factor. The stranger the coincidence, the higher the K number. I believe he had self-published a book on the subject, called 'K, the Power of Coincidence,' or something like that."

We both laughed. I still keep in touch with Barry, who can now be heard as much over the Internet as on radio.

In 2002, a radio industry publication, Talkers magazine, ranked Barry Farber the 9th greatest radio talk show host of all time.

Why Me?

A casual observer of my brief radio career might wonder why Ivan Sanderson went through all the trouble of getting me on the air. Generally, when a student interviews a celebrity, the only dramatic effect is an intense urge by said celebrity to conclude the interview as quickly as possible and go back to airing his or her personal problems in the pages of tabloids. Why the special treatment in my case? I think perhaps a story Ivan told us that evening explains everything.

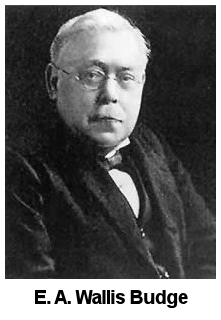

When Ivan was a boy, he was wandering around the exhibits of Egyptian artifacts at the British Museum, pen and paper in hand, attempting to compile a complete list of the Egyptian pharaohs.

When Ivan was a boy, he was wandering around the exhibits of Egyptian artifacts at the British Museum, pen and paper in hand, attempting to compile a complete list of the Egyptian pharaohs.

An old man patiently watched him for a while, then came over to him and asked what he was doing. Ivan explained his mission.

The old man said, "I work here. Come with me, I'll show you our collection." And indeed he did, spending more than three hours showing young Ivan the museum's immense, glorious collection of Egyptian artifacts that the public rarely if ever gets to see. While walking along with him, he also introduced Ivan to various people working there. When this extraordinary personal tour ended, Ivan thanked the mystery man and asked him his name.

"Oh, I'm Wallis Budge," he said.

It was Sir Ernest Alfred Thompson Wallis Budge (July 27, 1857 – November 23, 1934) a great Egyptologist, Orientalist, and philologist who worked for the British Museum and published many works on the ancient Near East. His translation of the Egyptian Book of the Dead greatly influenced the works of William Butler Yeats and James Joyce. Despite improvements in Egyptian language translation over the years, many of his works are still in print.

"It was as if he recognized something in me," said Ivan, "and on the off-hand chance that I could possibly grow up to be a great Egyptologist too, he spent the time introducing me to all the wonders the field had to offer."

Well, Yours Truly can't say that he ever made any advances in the fields studied by Ivan Sanderson, but in retrospect it is gratifying to see that, in a world of greed, backstabbing and all-around exploitation, immensely generous souls such as Wallis Budge and Ivan Sanderson continue to pop up now and then in history to pass on the torch.

And so now, decades later, I repay Ivan with this online tribute, one that may rekindle the general public's interest in this most remarkable, nearly forgotten individual.